… some people we love without understanding, without knowing, without expectation - simply and with joy in their company and concern for their happiness:

A few days ago, I posted a request…

Shelley if you’re out there. I need pictures. Beverly Pepper has work in the Laumeier International Sculpture Park in St. Louis. Cromlech Glen. Can you run over there and take a bunch of pix so we can all enjoy it?

She took the assignment. I’m pleased to be Shelley’s first commercial photography patron. As she says,

Frank had asked me for an interview, and in its place I gave him this because I’m a writer and a photographer, and you can learn all you want to about me from my written words and my photographs. Anything else I would say would just be facts. Of course, one is not supposed to be changed by an interview. At least, that’s what I’m told. However, by asking me for photos of Cromlech Glen, Frank’s changed who and what I am, because now I’m a photographer who has taken photos on assignment. If Frank sends me a dollar, a crisp, new dollar that I can frame as my first dollar earned as a photographer, I will then be a Professional Photographer. And if Frank publishes at least one of my photos at his site, I will be a Published Professional Photographer. And writer, too, of course, but this interview hasn’t changed that.

Some of the pictures she took and the narrative that accompanied the images is presented below. Here we have nominally…

The Shelley Powers Interview

Shelley Powers - on Assignment to Cromlech Glen

I think the reason I like the sculptures at the Laumeier Sculpture Park so much is because they’re living art. You can go up to any of pieces and hit it as hard as you want and the resulting sound — dirt hill, metal tube, wooden board, or old tire — will fill the valley and no one will come running, telling you that you can’t touch, mustn’t touch, that it’s art, and therefore out of bounds from lesser mortals. It’s truly living art, meant to be climbed on and explored and felt and touched.

Of course, not everything can be hit with equanimity, as I found when one of my favorite pieces, the Triangle Bridge over the Stream, was closed off because the glass sides had been smashed in. I’d like to think the wreckage was the result of weather or trees or just the forces of time on the sculpture; but it looks to have been kicked in and beaten, beaten fiercely, and not by someone who wanted to experience art. I can imagine someone coming down in the darkness and kicking at the glass, kicking and kicking, and feeling savage glee as the panes are cracked and smashed. The piece is secluded enough that they may have come during the day, but it doesn’t matter — that kind of person carries darkness within them.

The work can be repaired, is being repaired, but I’m glad I had a chance to see it now. There was something about its current state of smashed and cracked glass that I found to be extraordinarily beautiful. The whorls and the fragments caught the light and reflected back the stream. The panes from one side were completely missing and the rusted bars that used to hold the glass held only emptiness and somehow, this seemed to be more important. The vandal ultimately fails, because though art can be destroyed, it can never diminished. Art is the opposite of truth, which can be diminished but never destroyed.

While I was looking at the bridge, three older teenage girls, out for a walk, crossed over the red tape clearly labeled “Danger”, that closed off the bridge. To go around would have taken five seconds, but to go around would have been safe, and therefore uncool. We think that only boys are foolhardy, and that girls don’t have a streak of stubborn foolishness. Girls do, but we were taught at a young age that we were

the nest builders and men are the hunters and that to show ourselves as strong, and as stupid, as the men would make us seem less desirable as mates. I wondered, if I had been a handsome boy, would they have crossed the bridge? I think they would, but they might have lingered a bit and maybe even horsed around a little and pushed each other to the edge of the bridge where the glass was fractured, and looked at me with sidelong glances to see if I was impressed. But I’m an older woman, taking photos of broken glass, and therefore invisible; and they were young and “Danger” to them meant being uncool, not being cut. I didn’t follow them across the bridge. I walked around.

The next exhibit, and one of my favorites, is a set of boxes that look like rough wooden caskets. The untitled work, by Ursula Van Rydingsvard, is haunting — perfect little caskets, all in a row. The juxtaposition of rough wood and careful alignment is exotic and compelling. About the work, the artist wrote:

“Perhaps I’m still reacting to the shock of coming to the < ?xml:namespace prefix = st1 />

At the end of this trail past the boxes was the target of my jaunt this evening: Cromlech Glen, by Beverly Pepper. This is the sculpture that Frank asked me photograph when he posted his request to me, me with a missing ‘e’ me. It’s also one of my favorites because it sits in an isolated glade surrounded by thick trees at the end of the trail and is a place where one can get away from people and sit and think without having to watch whether one is talking to oneself, which only works well in

The exhibit is two mounds of dirt, with sandstone steps leading to the top of each, both of which are normally covered in Scotch Bloom. However, when I got to the park, the winter wrap of straw had been laid down on the mounds’ sides and tops to keep them from deteriorating over the winter. As with the fractured glass in the triangle bridge, I was glad because I’ve found the sculpture, covered with straw, to be more interesting than when the work is its normal soft, blue-green summer self.

A blue ribbon was drawn across the path to the sculpture with a sign that the exhibit was closed for renovation. This time, though, I was not held back by ribbon and entered the field around the mounds to complete my assignment and take my photos — do or die — though I did stay off the carefully covered dirt.

When you walk behind the mounds, you can see how gracefully they work together, and with their surroundings. There’s a hint of the mystical in Pepper’s creation, not surprising as she meant these works to form backdrops for everything from quiet meditation, to dances, and poetry readings. Can’t you imagine walking down a long wild forest trail, further and further away from the parking lot and the roads and the

traffic, and to come upon these two mounds, steps leading to the top, completely isolated from the rest of the park. To one side is a stream, with the ever present quaint Missouri stream bridge; on the other side of the trees is some kind of airport, though I have no idea of which one it is because I’ve never been able to find it. One time, though, when I was walking through the park, I topped a hill just as a jet was taking off and I could see it clearly through the trees, huge, close, and on a

level with where I was standing. When I told others, they had no idea of what I was talking about, and I had no photo to prove my story.

Perhaps what I saw was the result of a vision quest, an image sent by the Little People. But a jet? What could that possibly mean?

Returning to the moment, I took several photos of the Glen for Frank, but I wanted to save room on my camera for some of my other favorites, such as the big red aluminum and steel work, The Way, by Alexander Liberman.

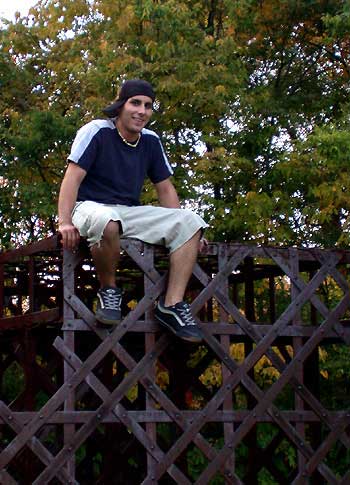

This sculpture is huge and I love to walk around it and touch it, bang it, climb it, and of course, photograph it. While I was trying another new angle — one can never have too many angles of The Way — three young men started climbing about on it, carefully because there’s little traction in the smooth metal.. They tired of sliding down its sides, and began to climb about another sculpture next to The Way, a new one with plenty of hand and foot holds for the energetic. The look appealed to me so much, I surreptitiously took their photo, and as they started getting down, I told the young man still on the work that I was a freelance writer, writing a story about Living Art for a publication called “Sandhill Tech”. Would he mind posing for me?

“Sure. What do you want me to do?”

“Just be natural”, I replied. And then after further thought, “unless that’s a dangerous thing to ask.”

He and his friends laughed and I took the picture. Unfortunately, my F-stop on the camera wasn’t quite on, and the light was failing and the photo didn’t come out as I hoped. The eyes aren’t clear, and I hate photos where you can’t really see the eyes of the people when they’re looking at the camera. However, living art also implies that art is made of living things that move and maybe I should send the photo to Frank

anyway. If I do, then meet Joe, because that’s my subject’s name.

Frank had asked me for an interview, and in its place I gave him this because I’m a writer and a photographer, and you can learn all you want to about me from my written words and my photographs.. Anything else I would say would just be facts. Of course, one is not supposed to be changed by an interview. At least, that’s what I’m told. However, by asking me for photos of Cromlech Glen, Frank’s changed who and what I am, because now I’m a photographer who has taken photos on assignment. If Frank sends me a dollar, a crisp, new dollar that I can frame as my first dollar earned as a photographer, I will then be a Professional Photographer. And if Frank publishes at least one of my photos at his site, I will be a Published Professional hotographer. And writer, too, of course, but this interview hasn’t changed that.

In fact, if I were Schroedinger’s Cat, Frank would not only have opened the box, he would have fed me cream, given me a catnip mouse, and a red leather collar and shiny heart shaped tag with “Fluffy” written on it.

Still, this isn’t a Frank Paynter interview if there isn’t sex in it in some way. So I have to finish this story/monologue/essay/autobiographical self-interview with the ride home from the Park. I stopped by the mall to buy a nightgown and robe, and

I’d like to say they were see-through chiffon and sexy lace and ribbons meant to be pulled, but they weren’t. They were soft, and gentle, and both were pink, though I have no idea of why I bought pink with delicate trim and embroidered roses. This isn’t me, but then, neither is wearing a robe or a nightgown.

But that’s not the sex talk I owe Frank.

The weather was warm tonight, warm enough to have both windows of the car open. An almost full Harvest Moon lit the night, wisps of clouds streaking across its face as I drove home. I played a particular song as I drove, “Gimme Some Lovin’” by the Spenser Davis Group. I played it loud, completely indifferent to any noise pollution laws — as flagrant a lawbreaker as those young girls and their flirtatious fling with

“Danger” and shards of glass. The cool breeze blew through my hair as I sped down the road, me driving my little Focus like it was a high precision Ferrari because, really, most of this is all a matter of mind.

Some say that sex is a way of reaffirming that we are alive. The act of touching and being touched, the intimacy, and the release, are all ways for us to celebrate life and, if we’re lucky enough, love with another person. But tonight as I drove down the road and listened to the music and felt the wind and the warmth of the night, I felt alive. Earlier when I walked in the Park and took the photographs, I felt alive.

Tonight, when I wrote this story, I felt alive.

I wish I could say that there was a handsome stranger with intense dark eyes and sensuous fingers — someone special, someone to hold, someone to experience that touch that’s more intimate than any act of sex can ever be — but it was just me, the night, and the Man on the Moon. Since my relationship with the Moon is strictly platonic, I have no story of sex to offer, and we’ll have to settle for my pink nightgown and the

summer night and walk in the park and call it, good-night.